SaaS Pricing is hard. PricingSaaS is your cheat code.

Monitor competitors, track real-time benchmarks, discover new strategies, and more.

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a little while, you will almost definitely recognize The Four Myths of Bundling. Written by Shishir Mehrotra, the post has become my go-to resource on bundling. I’ve found myself revisiting it over and over, learning something new every time.

Shishir is the CEO of Coda, which is a doc for teams that blends the best of docs, spreadsheets, and applications into a single surface. Before founding Coda, he led Product, Design, and Engineering teams at YouTube, and is on the Board at Spotify. I don’t think it’s hyperbole to say that across his experiences, he has developed a philosophy around bundling. I initially came across him through his interview on Invest Like the Best, which I highly recommend.

Shishir’s ideas have informed several of my posts, including The New York Times Bundling Strategy and The Past, Present, and Future of ESPN+. Put simply, once you read The Four Myths of Bundling, it’s hard to think about bundles through any other lens.

Earlier this month, I tagged Shishir in a tweet about Disney’s bundle, and in his reply, he referenced a SuperFan Test that he uses when evaluating bundle pricing. Needless to say, I was intrigued and asked if he would be down to connect to tell me more. He agreed, and over Zoom, he took to Miro to give me a peek inside his toolkit.

Today, I want to share what I learned, and apply Shishir’s frameworks to a few recent bundles.

Definitions

Before jumping in, let’s cover some quick definitions. When thinking through any bundle, Shishir categorizes the general population into 3 categories:

SuperFans: Consumers who would:

Pay retail for a good, and

Have the activation energy to find it

CasualFans: Consumers who lack one of the two SuperFan criteria above

NonFans: Consumers who ascribe zero (or perhaps negative) value to having access to the good

Using Spotify as an example:

A SuperFan would be a paid subscriber

A CasualFan would be a free subscriber, and

A NonFan would be someone who doesn’t use Spotify at all.

Armed with these definitions, we can take Shishir’s first step in evaluating a bundle: the 9-Box Test.

The 9-Box Test

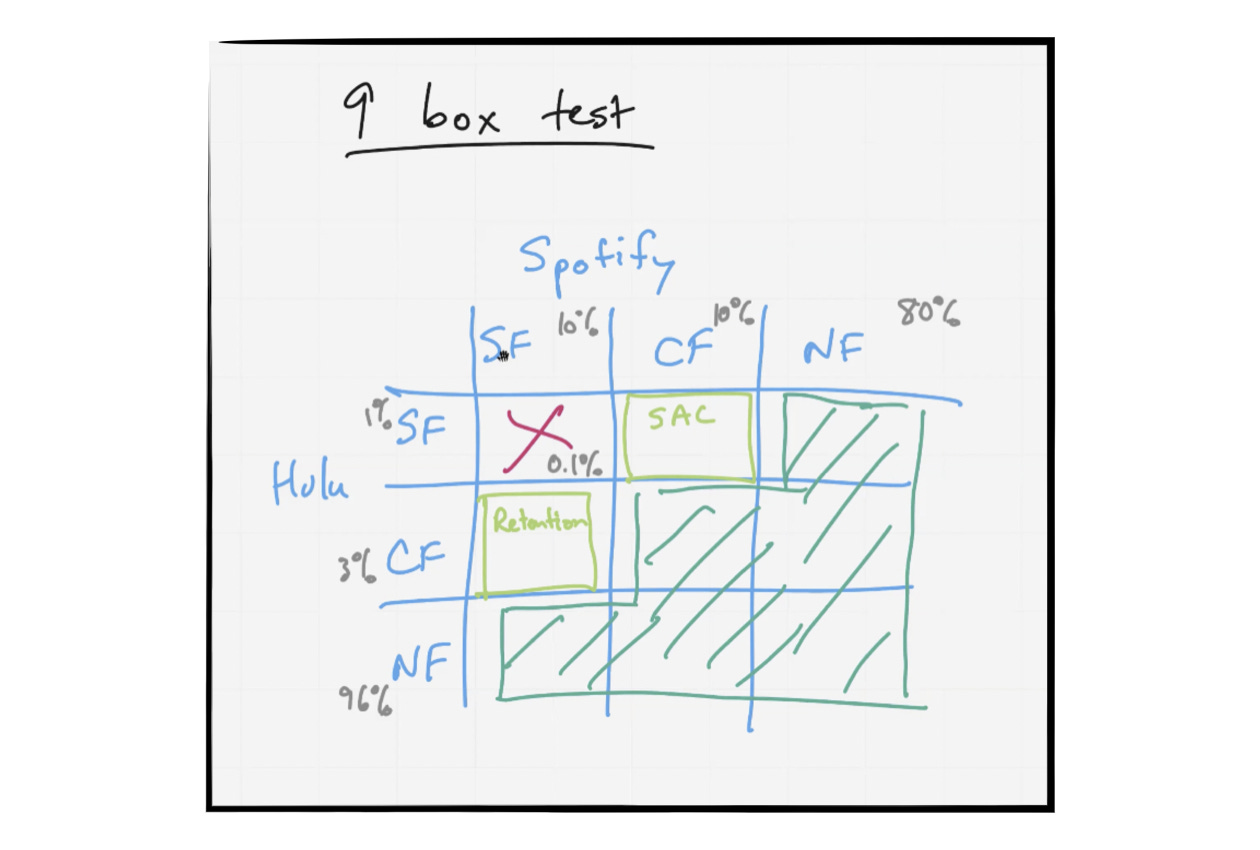

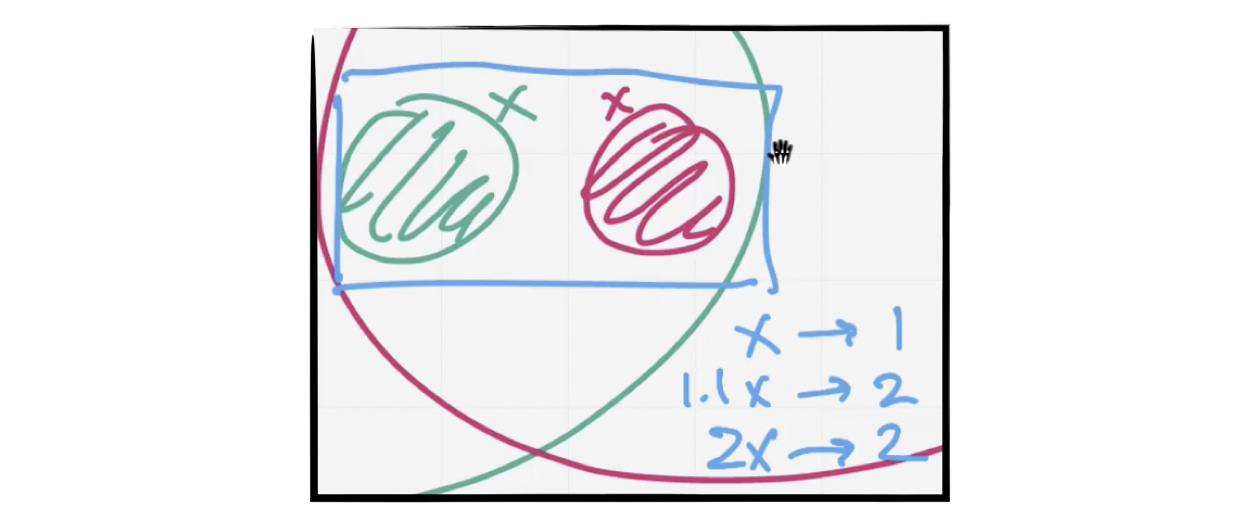

When evaluating any bundle between two products, Shishir applies a framework called the 9-Box test to help visualize the market opportunity.

To perform the test, all you have to do is line up SuperFans, CasualFans, and NonFans of each product on their respective axis. To illustrate the test, Shishir used an example of a bundle between Spotify and Hulu.

Here’s what it looks like:

The percentages refer to rough estimates of how much of the American population comprise each group. By multiplying these percentages you can roughly approximate the percentage of the population reflected in each box, and determine where the biggest opportunity lies for a given bundle.

The 9-Box Test also helps you visualize which consumers to optimize for when considering the goals of your bundle. Using the test from Spotify’s perspective, let’s look at the dark green boxes first.

Shishir considers the dark green boxes to be representative of economic opportunity for the whole industry. These boxes represent consumers that might not be interested in one or both of these products individually but may be attracted to the bundle for the perception of value that it creates.

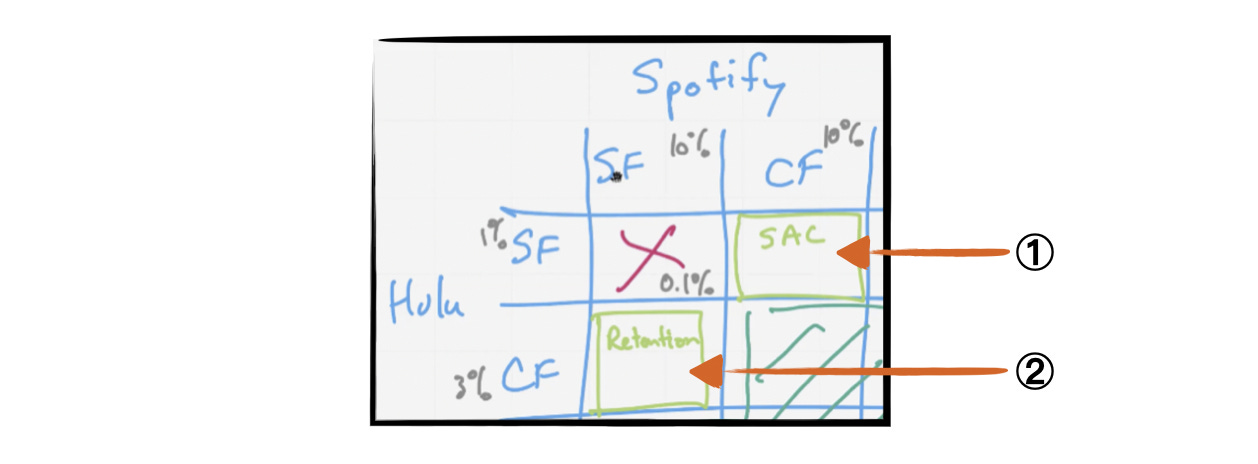

Next, are the light green boxes, or the intersections between SuperFans of one product and CasualFans of the other. These boxes each serve a specific purpose.

From Spotify’s perspective, optimizing for Spotify CasualFans, and Hulu SuperFans lowers Subscriber Acquisition Costs. This helps attract consumers that otherwise either wouldn’t be willing to pay retail for Spotify or have the activation energy to pursue a subscription.

Alternatively, optimizing for Spotify SuperFans and Hulu CasualFans helps drive retention by giving paid subscribers another reason to stick with Spotify.

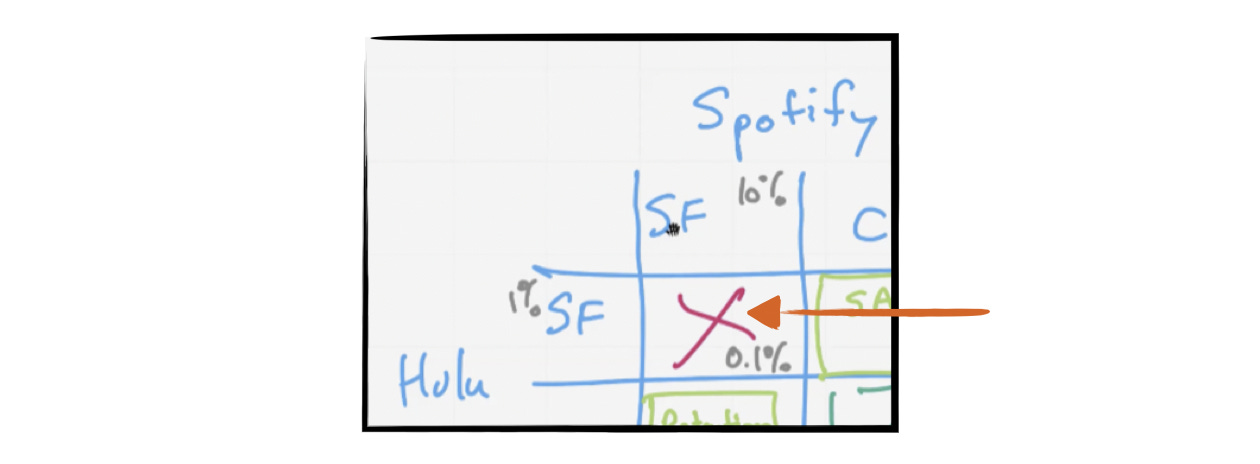

The last box to evaluate is the one with the big, red ‘X’. This is the intersection of SuperFans of both products.

Critically, you want to make sure you are not optimizing your bundle for this box. Since these customers will pay retail for each product individually, there’s nothing to be gained by attracting them with a bundle.

Unfortunately, Shishir explained, this is the exact box most people unintentionally price their bundles for.

The risk of offering a bundle that requires you to be a SuperFan of more than one product is that with each subsequent SuperFan requirement, you’re further limiting the pool of consumers that might perceive value in the bundle.

While it’s not always a bad thing to launch a bundle with multiple SuperFan requirements, it’s important to understand what you’re doing beforehand so you can measure success accordingly.

This is where the SuperFan test comes in. Let’s first define the SuperFan test, then use it to examine three bundles:

Spotify + The New York Times

Apple One

Spotify Premium for Students

The SuperFan Test

Shishir’s SuperFan test is pretty simple. When evaluating any bundle, he asks, “For how many products in the bundle do I have to be a SuperFan to justify paying for the bundle?”

As referenced above, one of the fundamental insights Shishir has learned across his bundling experiences is that when people bundle two products together, the first instinct is to offer it at a cost that only appeals to SuperFans of both products.

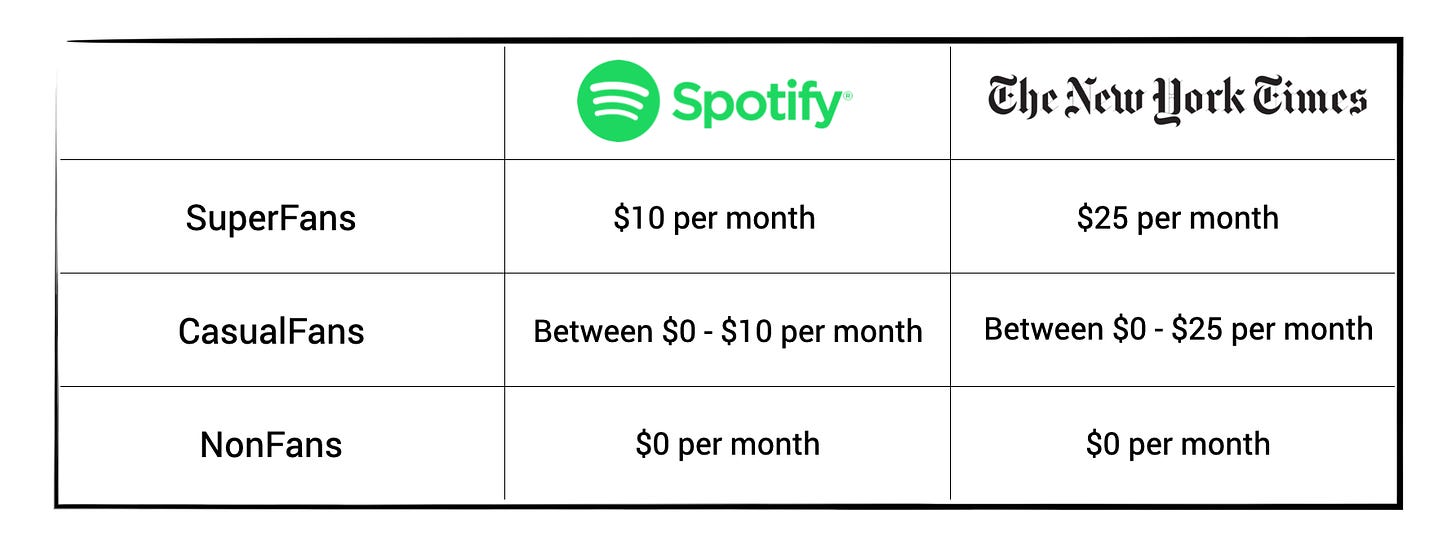

To illustrate this idea, he walked me through a bundle he worked on a few years back at Spotify, where they offered a bundle of Spotify and the New York Times for ~$5 per week (~$21 per month).

At the time, Spotify was $10 per month, and the New York Times was ~$25 per month. At ~$21 per month, the bundle was priced as a way to save 20% on a Times subscription with the added benefit of Spotify.

On paper, this looks like a great deal. The total price of the two subscriptions alone is $35 per month. The bundle saved subscribers ~$15 off that price!

What Shishir quickly realized, however, is that not all consumers value each of these products at full price. Utilizing the definitions above, consider how each type of consumer values Spotify and the New York Times:

You quickly realize that to find the bundle enticing, a consumer has to value both Spotify and the New York Times at $10 per month or greater. This is a tall order.

Shishir attributes part of the problem to the challenge most consumers have calculating price elasticity themselves. Here’s Shishir:

From the perspective of the team providing the offering, you tend to have some sense of the elasticity curve. At Coda, we have some understanding that if we were to lower the price to X, it would have this impact on demand. However, most consumers that look at Coda tend to think about price as part of the product. They have a very hard time calculating their willingness to subscribe at different price points, for example, at $10 per month, I’m 90% willing to subscribe, and at $9 per month, I’m 95% willing to subscribe. It’s very hard for people to do elasticity math themselves.

To visualize this dynamic, he drew out an example of a bundle of two products, priced the same, with zero SuperFan overlap.

In this hypothetical bundle, the price of one of these products is X, and the price of both is 2X. If you were to price the bundle at 1X, then you would only have to be a SuperFan of one to see value in the bundle, and if you price the bundle at 2X, then you would have to be a SuperFan of two.

Shishir’s key insight here is that pricing at any point in between 1X and 2X actually rounds the SuperFan requirement much closer to two than you might think.

Shishir contends that to value that second product, the consumer really has to understand and appreciate it. This insight helped him contextualize the limited success of the Spotify and New York Times bundle, and provided a framework for evaluating future bundles.

SuperFan test in hand, let’s take a look at two more...

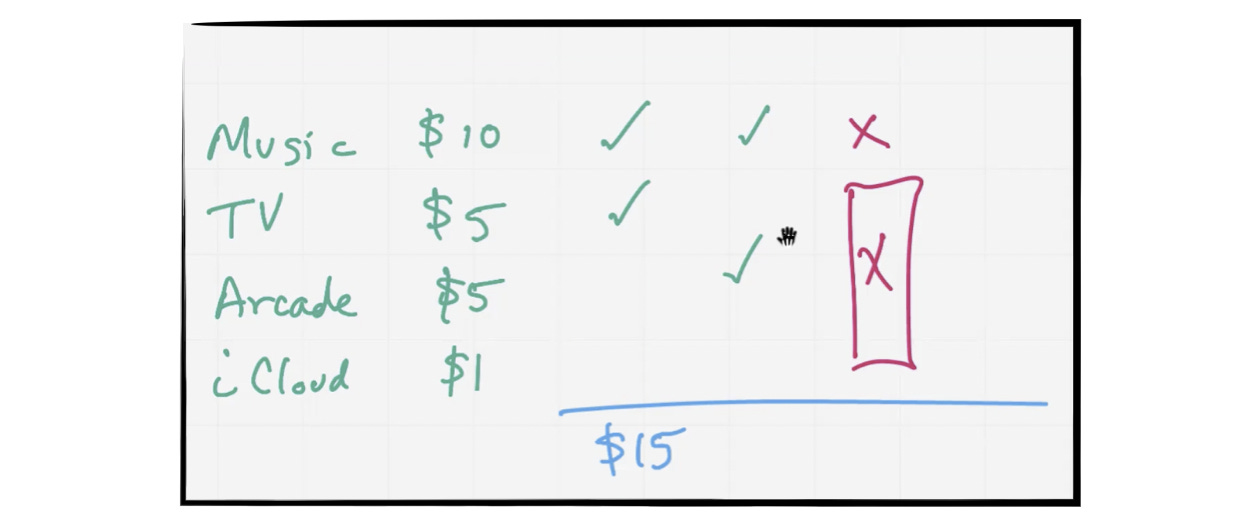

First, take Apple One, which is priced at $15 per month, and includes Apple Music, Apple TV+, Apple Arcade, and iCloud. Using the SuperFan Test, Shishir walked me through how consumers might justify paying for the bundle.

Ultimately, in order to find value in the bundle, at the very least, someone has to be:

A SuperFan of Apple Music

A SuperFan of one of Apple TV+ or Apple Arcade, and

A CasualFan of iCloud

This gives the Apple One bundle a SuperFan test score of 2, which means you have to be a SuperFan of two products in the bundle to find it compelling enough to purchase.

The thing is, if someone is a SuperFan of two of the products that bring the price to $15, that only gets them to break-even. They still need to have some interest in at least one of the other products in the bundle.

Because of this, Shishir argues that you could even give the Apple One bundle a SuperFan score of 3. Looking at it through a purely economically motivated lens, someone would need to ascribe value to iCloud as well, which would round the SuperFan score up to 3.

This is a high bar to clear, and critically, if someone is not a SuperFan of Apple Music, there is no way for the $15 price to make sense.

Because of this, Shishir considers Apple One to be an Add-On Bundle.

Essentially, Apple is saying if you are already a SuperFan of Apple Music, here’s a good deal on some of our other products. Add-on bundles like this have limited utility in driving new market-share, but can be powerful retention tools.

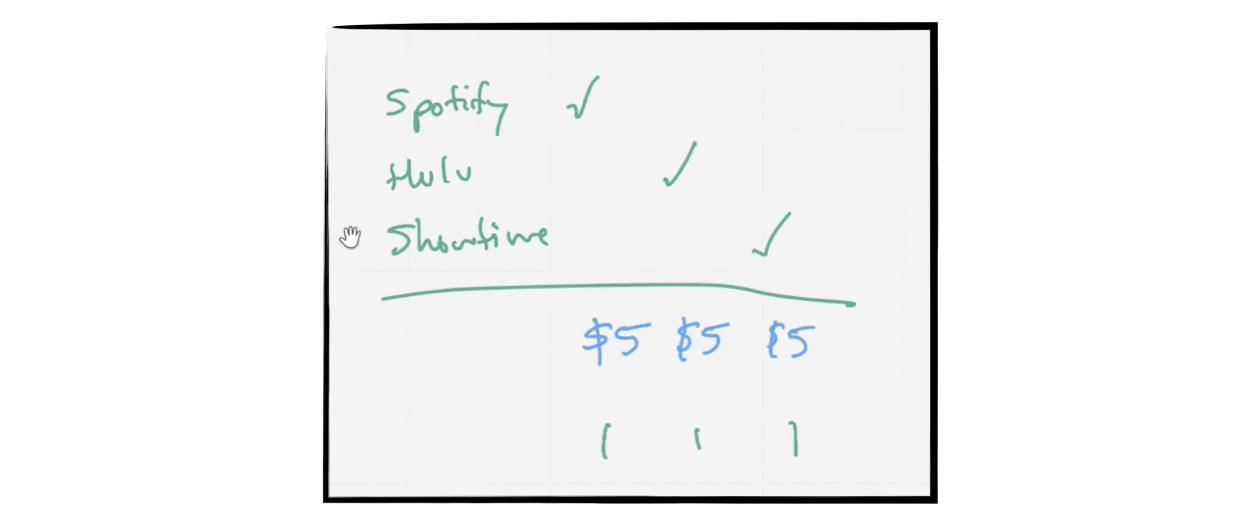

Alternatively, let’s look at an example of a bundle with a lower bar to clear, the Spotify Premium bundle for students.

This bundle gives students the chance to subscribe to Spotify, Hulu, and Showtime for $5 per month. Since each of these products has a retail price of at least $5 per month, you only need to be a SuperFan of 1 product to justify paying for the bundle.

This makes it much easier for the bundle to appeal to a given consumer and gives each company a chance to tap into a broader base of prospective customers that they can convert into genuine SuperFans.

Back to the Original Bundle

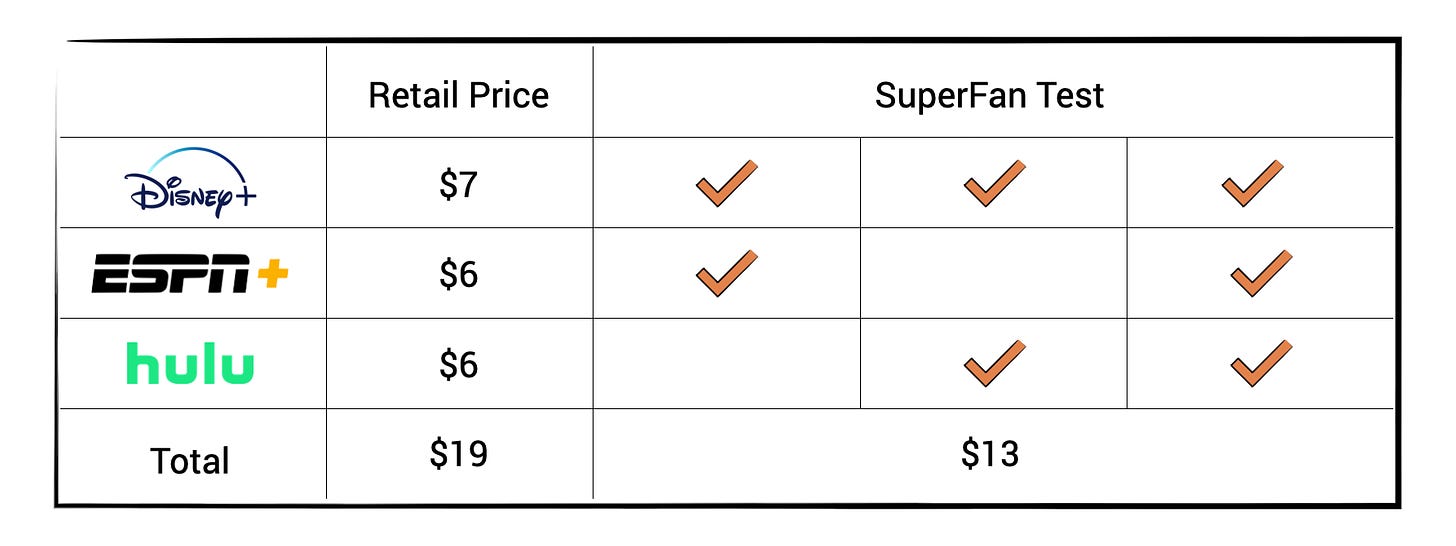

My original Twitter exchange with Shishir was in reference to Disney’s bundle that includes Disney+, ESPN+, and Hulu. At the time, here’s how the three products were priced, and the ways to justify the bundle price.

Ultimately, there are three ways to make the bundle work, but two of them only get you to break-even. To find value in the Disney bundle, you need to be a SuperFan of Disney+, one of either ESPN+ or Hulu, and ascribe some value to the other offering.

Based on Shishir’s logic above, this means that while the true SuperFan test comes out to 2, you can make the argument that it’s 3 since being a SuperFan of two only gets you to breakeven.

It seems like Disney might realize this.

In August, they raised the price of ESPN+ by $1 per month, and they recently announced they’ll be raising the price of Disney+ by $1 per month next year. If they continue raising prices for individual subscriptions, while holding the bundle price at $13, the value perception will get better and better.

Needless to say, chatting with Shishir re-framed my perspective on effective bundle pricing. Next time you’re evaluating a bundle, try pressure-testing it with the 9-Box Test and the SuperFan Test. The 9-Box Test will help frame the addressable market for the bundle, and the SuperFan Test will help determine if it’s priced realistically to achieve your goals.

Enjoying Good Better Best?

If you enjoyed this post, I’d love it if you hit the like button up top, so I know which posts are resonating most!

If you have feedback, I’d love to hear it - hit me up on Twitter.